|

| The author's father, Charles Keeler |

I first published this in Indian Country Today in 2013. I've been recently thinking about my dad a lot. We lost him within a week of being diagnosed with Stage 4 Cancer. It's something I'm still processing. The anger, the feeling he was stolen from us. But he was a great dad, an extraordinary thinker, and really smart. I certainly look like him, more so than I resemble my mom. I write to understand the complexity of my familial experiences and diversity. My father's experience growing up mixed-blood (5/8ths Ihanktowan Dakota according to the government) on the Yankton Sioux Reservation left him with conflicted feelings. His own father, my grandfather Edison Keeler (3/4 Dakota, according to the government), had been brutally beaten to death in police custody when he was a teenager. My mother's experience growing up on the Navajo Nation was very different. Perhaps in many ways, more secure and protected from the overt racism my dad's people faced outnumbered on their own reservation due to allotment. So I write to understand a complicated legacy and my own experiences, which are different from those of my parents.

Almost Trayvon

by Jacqueline Keeler

When I heard of George Zimmerman's acquittal, my thoughts went not to my 10-years old son but to my dad when he was 18-years old. I avoided coverage of the trial because I knew the unrepentant Zimmerman defense would blame his victim Trayvon Martin, for his own death. I knew that listening to it would mean listening again to the same old ugliness that has plagued this country since Columbus first landed on an island in the New World he named San Salvador, "the savior." A name I imagine that may self-servingly encapsulate Zimmerman's view of himself and his volunteer work as a member of the neighborhood watch. He said, referring to the victim," These guys all get away," and after he shot the 17-year old, "I feel it was all God's plan." I say, it all sounds too familiar.

And so it was after the verdict I thought of my dad when he was 18, unarmed and facing down a gun pointed at him by a white man he had known his entire life. This was during the Jim Crow era in the United States, and my dad was not Black but a mixed-blood Dakota Sioux Indian.

It's funny to think that in most South Dakota border towns, even today, Zimmerman--who looks more Indian than white-- would be subject to the exact same scrutiny that he gave Trayvon Martin, that he could even be struck down under very similar circumstances. The line in the sand of "race" or "caste" is a tricky one as you move around the country; which side you fall on is an educated guess at best, but getting it right can mean the difference between life and death.

My dad was raised in Lake Andes, a white town located on the Yankton Sioux reservation. His mixed-blood family occupied a strange nether world, neither white nor Indian. My dad recounts having the white folks boo him when he dribbled a basketball during a game, and then on the other side, the full-bloods would boo him, too. His dad, whose father and uncle had owned the first car dealership in that part of South Dakota (yes, Indians did things like this), was best friends with the Sheriff, and the two of them had even engaged in bootlegging together during Prohibition. My grandmother, who could pass for white (her Dakota name was "Green Eyes"), regularly had her hair done at the beauty salon on main street. I did not learn until a few years ago that most Indian people of that time were not allowed to get their hair cut in town or play snooker at the bar with the Sheriff.

But despite this seeming acceptance by the white community, things began to unravel for our family. My grandfather died under suspicious circumstances; he was found drowned in the Missouri River. My mother claimed she heard from her in-laws that he had been beaten to death by white friends for his paycheck. When I asked my dad, he just shook his head, "No," he said, "It was a work accident, the dam," but his voice was shaking, and he looked like I had never seen him before: raw with grief. I can still remember as a child asking a dining room full of aunts and uncles and my grandmother, "What about grandfather? Tell me about my grandfather," and being greeted by complete silence. My dad was 15 and was sent alone to identify his father's body for the authorities. My grandfather's body had been so horribly disfigured he could only identify him by a mole on his ankle.

It was only recently that he told me why he joined the Army and left his hometown for good: he had been captain of the Lake Andes High School football team (the first Indian in 25-years), Snowball King, and a straight-A student. Then, suddenly the white men in town, men like the Sheriff who had been good friends with his father, began to act as if they were afraid of him. It culminated in the Sheriff pulling his gun without cause on my dad while he was walking down the street. He had been given two choices: leave town immediately or go to jail. He joined the Army, went to college, married my mom, and raised his children proud to be Indian far away from Lake Andes.

Many people look back to that time before the Civil Rights movement as a period of greater "law and order" in this country. Even my grandmother once said of that time, "everyone got along." I asked my dad, "Did everyone really get along?" A part of me wanted to believe it, preferring it to the constant threat of violence that hung over us in every generation. "She said that?" he shook his head and said dismissively, "Well, everyone got along because everyone knew their place!"

|

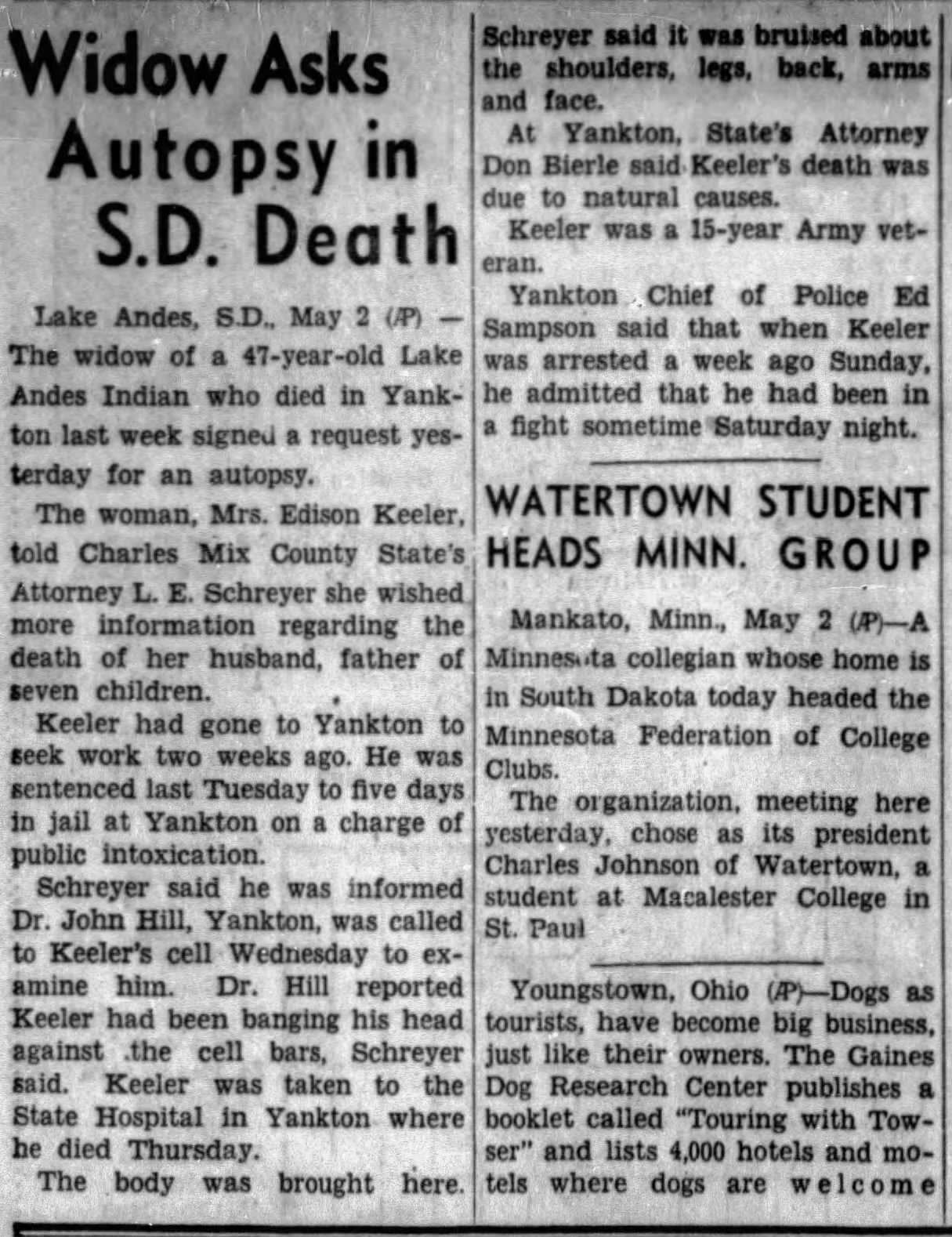

| Argus Leader, May 2, 1955 |

And my grandmother knew better. In a news article dated May 2, 1955, in the Argus Leader titled "Dead Man's Widow Asks an Autopsy," my grandmother, identified as "the widow of a Lake Andes Indian," pleads for a second independent autopsy of my grandfather after his murder. My grandfather is described as "banging his head against .the cell bars" and 'bruised about the shoulders, legs, back, arms and face." My family says he went to the police in Yankton (a nearby White city that bears our tribe's name) to report he had been robbed, and they arrested him and beat him to death.

In the Jim Crow era, African American families clung to their Green Books which told them where it was safe to stay when traveling and which town to avoid after sundown. No such book existed for Native Americans in the South. One of my dad's summer jobs was as a truck driver, and one of his deliveries took him to the Deep South. At a gas station, he was confronted with a choice of restrooms, one for White and one for Colored. My dad's hair is black, but his skin is lighter due to his mixed ancestry; baffled, he asked the white owner which he should use. The old man looked at him impatiently and waved him off, "White, of course." "But, I'm not white," my dad insisted. And with that, the old man threw up his hands and stormed off.

When my dad joined the Army, he scored very high on an IQ test and was placed in an elite intelligence unit. Everyone else was older than him, and many were Ivy League graduates. They mentored him, gave him books to read, and encouraged him to go to college. By the time I knew him, the teenager driven out of his hometown by an armed adult had long ago been replaced by a confident adult, a steady and loving father, and a husband.

As an engineer at a National Laboratory, my father held the highest security clearance available to civilians. This youth who had once been driven out of town by gunpoint was entrusted with our nations' secrets for his entire adult life. One day two FBI agents came to question him. The younger noted, "I see you have an arrest here. Can you explain it?"

My dad said, "I'm Indian."

"What do you mean?" The younger man was confused.

My dad said nothing more, but the older man nodded at him and told the younger man, "We're done here." "But what about the arrest?" "We're done."

He knew. Everyone did; they all knew their place.

"They arrested me," he explained to me, "because the town needed young men to clear the roads of snow after a blizzard. That's just what they did in small South Dakota towns back then, they arrested all the young Indian men in town and put them to work."

My dad's ethnicity rarely came up in the larger world away from the reservation. When it did, most often, like Zimmerman, people asked if he was Jewish because of his curly hair, Dakota features, and his large, round European eyes, which colored black look Middle Eastern. Ironically, shortly after 9-11, he was detained when he and my mother boarded a plane. The TSA agents asked him numerous questions about his racial identity because they thought he was an Arab terrorist.

When they finally let him go, he asked where my mom was, and the flight attendant said, "Oh, you mean that Asian woman?" My mom is a full-blooded Navajo. Once, she had been refused entry into the United States from Canada (she was visiting Niagara Falls) as a college student during the Vietnam War. They thought she was a Vietnamese spy, and they called the Bureau of Indian Affairs to confirm her identity as an American Indian. Not only do we look like the enemy, but enemy-held territory is still called "Indian Country" in military circles. In the Iraq War, soldiers referred to enemy territory as "Indian Country." For example, former Marine Second Lieutenant Ilario Pantano's defense attorney explained his murder of two Iraqi captives: "This is Iraq, Indian Country is where bad guys do things."

Zimmerman, the killer, is brown but has fully embraced the worldview of his white father and the protection afforded by their whiteness. The blank slate of being "blanca" upon which no profile is written provides a modicum of security in this world where the boundaries of "Indian Country" are constantly shifting. And the Trayvon Martins of the world must rely on the luck of whether the white man holding the gun chooses to shoot or not. Looking at my father's life after that incident, I have to wonder what Trayvon's life would have been like? Would he have married and raised children? We will never know. That future has been taken from him, his family, his future children never born, his partner never loved.

This ruling is once again telling us to "know our place." Fifty years ago, Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote in "Letter from a Birmingham Jail," "Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly." And today, in the 21st century, a generation of Black youth are admonished not to frighten decent White folk into killing them. And the White folk have been re-gifted with the cover the law for murder. How did we arrive full circle at this point? What does it mean for my son, brown-skin from his Diné grandmother and who has his grandfather's curly black French hair and Dakota features? Will he inspire fear once he is grown tall and strong like his Dakota and his father's Mohawk ancestors? What then?

I'm disappointed in my country, in my generation, for not doing better for our children. We were born after the dream of the Civil Rights Movement was made real, and we have done nothing with that great inheritance but fritter it away and harbor ignorance of one another. Ignorance Juror B-37 proudly proclaimed loudly in her interview with Anderson Cooper on Monday.

The funny thing is, I don't think my dad ever told me what choice he made that day in the Jim Crow South, to use the white or colored bathroom. I imagine from the disgusted tone he told the story in he chose the colored bathroom because he didn't want to have anything to do with the old white man telling him the rules of the White Supremacist game. Whatever his choice, I hope no one ever has to make again.

No comments:

Post a Comment